Science and Research

By MedExpert Science & Research | Mar 20, 2020

Q.

Does chloroquine provide us with hope for treatment of COVID-19 and is there precedent that chloroquine can treat viruses.

A.

Yes, there is hope.

Chloroquine, a widely-used anti-malarial and autoimmune disease drug, is a form of Quinine that was made in Germany by Bayer in 1934. The drug has a long history of use and is readily available. Chloroquine is known to block virus infection by decreasing the acidity (or increasing the pH) required for a virus to fuse with a cell, as well as interfering with cellular receptors of SARS-CoVAs (Note: COVID19 or coronavirus (2019-nCoV), are officially referred to in medical journals as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 or SARS-CoV-2).

As reported by Christian Devaux on March 12, 2020 in the International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents, chloroquine possesses antiviral activity in laboratories against viruses as diverse as rabies, poliovirus, hepatitis A virus, influenza A and B viruses, influenza A H5N1 virus, Dengue virus, Zika virus, and others. The antiviral properties of chloroquine described in the laboratory have sometimes been confirmed during treatment of virus-infected patients but have not always been reproduced in clinical trials.

A recent paper by Dr. Manli Wang and Gengfu Xiao published in Cell Research reported that both chloroquine and the antiviral drug remdesivir inhibited SARS-CoV-2 in the laboratory and moved to assess these drugs in patients suffering from COVID-19.

According to a recent report by Dr. Gao published in Bioscience Trends approximately 100 infected Chinese patients treated with chloroquine experienced a more rapid decline in fever and improvement of lung computed tomography (CT) images and required a shorter time to recover compared with control groups, with no obvious serious adverse effects.

Yesterday anecdotal information was shared by a woman whose husband’s infection with SARS-CoV-2 was greatly improved as a result of drug treatment.

More information can be found below.

New insights on the antiviral effects of chloroquine against coronavirus: what to expect for COVID-19?

Christian A.DevauxabcJean-MarcRolainacPhilippeColsonacDidierRaoultac

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105938Get rights and content

International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents

Abstract

Recently, a novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV), officially known as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), emerged in China. Despite drastic containment measures, the spread of this virus is ongoing. SARS-CoV-2 is the aetiological agent of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) characterised by pulmonary infection in humans. The efforts of international health authorities have since focused on rapid diagnosis and isolation of patients as well as the search for therapies able to counter the most severe effects of the disease. In the absence of a known efficient therapy and because of the situation of a public-health emergency, it made sense to investigate the possible effect of chloroquine/hydroxychloroquine against SARS-CoV-2 since this molecule was previously described as a potent inhibitor of most coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-1. Preliminary trials of chloroquine repurposing in the treatment of COVID-19 in China have been encouraging, leading to several new trials. Here we discuss the possible mechanisms of chloroquine interference with the SARS-CoV-2 replication cycle.

1. Introduction

Chloroquine is an amine acidotropic form of quinine that was synthesised in Germany by Bayer in 1934 and emerged approximately 70 years ago as an effective substitute for natural quinine [1,2]. Quinine is a compound found in the bark of Cinchona trees native to Peru and was the previous drug of choice against malaria [3]. For decades, chloroquine was a front-line drug for the treatment and prophylaxis of malaria and is one of the most prescribed drugs worldwide [4]. Chloroquine and the 4-aminoquinoline drug hydroxychloroquine belong to the same molecular family. Hydroxychloroquine differs from chloroquine by the presence of a hydroxyl group at the end of the side chain: the N-ethyl substituent is β-hydroxylated. This molecule is available for oral administration in the form of hydroxychloroquine sulfate. Hydroxychloroquine has pharmacokinetics similar to that of chloroquine, with rapid gastrointestinal absorption and renal elimination. However, the clinical indications and toxic doses of these drugs slightly differ. In malaria, the indication for chloroquine was a high dose for a short period of time (due to its toxicity at high doses) or a low dose for a long period of time. Hydroxychloroquine was reported to be as active as chloroquine against Plasmodium falciparum malaria and less toxic, but it is much less active than chloroquine against chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum owing to its physicochemical properties. What is advantageous with hydroxychloroquine is that it can be used in high doses for long periods with very good tolerance. Unfortunately, the efficacy of chloroquine gradually declined due to the continuous emergence of chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum strains [5]. Chloroquine is also utilised in the treatment of autoimmune diseases [6]. Yet the activity of the molecule is not limited to malaria and the control of inflammatory processes, as illustrated by its broad-spectrum activity against a range of bacterial, fungal and viral infections [7], [8], [9], [10]. Indeed, in the mid-1990s, due to its tolerability, rare toxicity reports, inexpensive cost and immunomodulatory properties [11], chloroquine repurposing was explored against human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and other viruses associated with inflammation and was found to be efficient in inhibiting their replication cycle [12].

Recently, a novel coronavirus emerged in the Chinese city of Wuhan in December 2019. After human coronavirus 229E (HCoV-229E) (classified in the genus Alphacoronavirus) and HCoV-OC43 (Betacoronavirus lineage 2a member) described in the 1960s, SARS-CoV-1 (Betacoronavirus lineage 2b member) that emerged in March 2003, HCoV-NL63 (Alphacoronavirus lineage 1b member) described in 2004, HCoV-HKU1 (Betacoronavirus lineage 2a member) discovered in 2005, and finally MERS-CoV that emerged in 2012 (classified in Betacoronavirus lineage 2c), the novel coronavirus is the seventh human coronavirus described to date as being responsible for respiratory infection. Evidence was rapidly reported that patients were suffering from an infection with a novel Betacoronavirus tentatively named 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) [13,14]. Despite drastic containment measures, the spread of 2019-nCoV, now officially known as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), is ongoing. Phylogenetic analysis of this virus indicated that it is different (∼80% nucleotide identity) but related to SARS-CoV-1 [15]. Because the world is threatened by the possibility of a SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, the broad-spectrum antiviral effects of chloroquine warranted particular attention for repurposing this drug in the therapy of the disease caused by SARS-CoV-2, named coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

2. Antiviral properties of chloroquine

In vitro, chloroquine appears as a versatile bioactive agent reported to possess antiviral activity against RNA viruses as diverse as rabies virus [16], poliovirus [17], HIV [12,[18], [19], [20]], hepatitis A virus [21,22], hepatitis C virus [23], influenza A and B viruses [24], [25], [26], [27], influenza A H5N1 virus [28], Chikungunya virus [29], [30], [31], Dengue virus [32,33], Zika virus [34], Lassa virus [35], Hendra and Nipah viruses [36,37], Crimean–Congo hemorrhagic fever virus [38] and Ebola virus [39], as well as various DNA viruses such as hepatitis B virus [40] and herpes simplex virus [41].The antiviral properties of chloroquine described in vitro have sometimes been confirmed during treatment of virus-infected patients but have not always been reproduced in clinical trials depending on the disease, the concentration of chloroquine used, the duration of treatment and the clinical team in charge of the trial.

Regarding coronaviruses, the potential therapeutic benefits of chloroquine were notably reported for SARS-CoV-1 [11,42]. Chloroquine was also reported to inhibit in vitro the replication of HCoV-229E in epithelial lung cell cultures [43,44]. In 2009, it was reported that lethal infections of newborn mice with the HCoV-O43 coronavirus could be averted by administering chloroquine through the mother's milk. In vitro experiments also showed a strong antiviral effect of chloroquine on a recombinant HCoV-O43 coronavirus [45]. Although chloroquine was reported to be active against Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in vitro [46], this observation remains controversial [47].

3. Potential antiviral effect of chloroquine against SARS-CoV-2

Because of its broad spectrum of action against viruses, including most coronaviruses and particularly its close relative SARS-CoV-1, and because coronavirus cell entry occurs through the endolysosomal pathway [48], it made sense in a situation of a public-health emergency and the absence of any known efficient therapy to investigate the possible effect of chloroquine against SARS-CoV-2. A recent paper reported that both chloroquine and the antiviral drug remdesivir inhibited SARS-CoV-2 in vitro and suggested these drugs be assessed in human patients suffering from COVID-19 [49].

Recently, the China National Center for Biotechnology Development indicated that chloroquine is one of the three drugs with a promising profile against the new SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus that causes COVID-19. Chloroquine repurposing was investigated in hospitals in Beijing, in central China's Hunan Province and South China's Guangdong Province. According to preliminary reports [50,51] from the Chinese authorities suggesting that approximately 100 infected patients treated with chloroquine experienced a more rapid decline in fever and improvement of lung computed tomography (CT) images and required a shorter time to recover compared with control groups, with no obvious serious adverse effects, the Chinese medical advisory board has suggested chloroquine inclusion in the SARS-CoV-2 treatment guidelines. As a result, chloroquine is probably the first molecule to be used in China and abroad on the front line for the treatment of severe SARS-CoV-2 infections. Although the long use of this drug in malaria therapy demonstrates the safety of acute chloroquine administration to humans, one cannot ignore the minor risk of macular retinopathy, which depends on the cumulative dose [52], and the existence of some reports on cardiomyopathy as a severe adverse effect caused by chloroquine [53,54]. A survey of SARS-CoV-2-infected patients for adverse effects of chloroquine therapy remains to be performed. However, chloroquine is currently among the best available candidates to impact the severity of SARS-CoV-2 infections in humans. Currently, at least ten clinical trials are testing chloroquine as an anti-COVID-19 therapy [55].

4. Mode of action of chloroquine

Chloroquine has multiple mechanisms of action that may differ according to the pathogen studied.

Chloroquine can inhibit a pre-entry step of the viral cycle by interfering with viral particles binding to their cellular cell surface receptor. Chloroquine was shown to inhibit quinone reductase 2 [56], a structural neighbour of UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 2-epimerases [57] that are involved in the biosynthesis of sialic acids. The sialic acids are acidic monosaccharides found at the extremity of sugar chains present on cell transmembrane proteins and are critical components of ligand recognition. The possible interference of chloroquine with sialic acid biosynthesis could account for the broad antiviral spectrum of that drug since viruses such as the human coronavirus HCoV-O43 and the orthomyxoviruses use sialic acid moieties as receptors [58]. The potent anti-SARS-CoV-1 effects of chloroquine in vitro were considered attributable to a deficit in the glycosylation of a virus cell surface receptor, the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) on Vero cells [59].

Chloroquine can also impair another early stage of virus replication by interfering with the pH-dependent endosome-mediated viral entry of enveloped viruses such as Dengue virus or Chikungunya virus [60,61]. Due to the alkalisation of endosomes, chloroquine was an effective in vitro treatment against Chikungunya virus when added to Vero cells prior to virus exposure [30]. The mechanism of inhibition likely involved the prevention of endocytosis and/or rapid elevation of the endosomal pH and abrogation of virus–endosome fusion. A pH-dependant mechanism of entry of coronavirus into target cells was also reported for SARS-CoV-1 after binding of the DC-SIGN receptor [62]. The activation step that occurs in endosomes at acidic pH results in fusion of the viral and endosomal membranes leading to the release of the viral SARS-CoV-1 genome into the cytosol [63]. In the absence of antiviral drug, the virus is targeted to the lysosomal compartment where the low pH, along with the action of enzymes, disrupts the viral particle, thus liberating the infectious nucleic acid and, in several cases, enzymes necessary for its replication [64]. Chloroquine-mediated inhibition of hepatitis A virus was found to be associated with uncoating, thus blocking its entire replication cycle [22].

Chloroquine can also interfere with the post-translational modification of viral proteins. These post-translational modifications, which involve proteases and glycosyltransferases, occur within the endoplasmic reticulum or the trans-Golgi network vesicles and may require a low pH. For HIV, the antiretroviral effect of chloroquine is attributable to a post-transcriptional inhibition of glycosylation of the gp120 envelope glycoprotein, and the neosynthesised virus particles are non-infectious [19,65]. Chloroquine also inhibits the replication Dengue-2 virus by affecting the normal proteolytic processing of the flavivirus prM protein to M protein [32]. As a result, viral infectivity is impaired. In the herpes simplex virus (HSV) model, chloroquine inhibited budding with accumulation of non-infectious HSV-1 particles in the trans-Golgi network [66]. Using non-human coronavirus, it was shown that the intracellular site of coronavirus budding is determined by the localisation of its membrane M proteins that accumulate in the Golgi complex beyond the site of virion budding [67], suggesting a possible action of chloroquine on SARS-CoV-2 at this step of the replication cycle. It was recently reported that the C-terminal domain of the MERS-CoV M protein contains a trans-Golgi network localisation signal [68].

Beside affecting the virus maturation process, pH modulation by chloroquine can impair the proper maturation of viral protein [32] and the recognition of viral antigen by dendritic cells, which occurs through a Toll-like receptor-dependent pathway that requires endosomal acidification [69]. On the contrary, other proposed effects of chloroquine on the immune system include increasing the export of soluble antigens into the cytosol of dendritic cells and the enhancement of human cytotoxic CD8+ T-cell responses against viral antigens [70]. In the influenza virus model, it was reported that chloroquine improve the cross-presentation of non-replicating virus antigen by dendritic cells to CD8+ T-cells recruited to lymph nodes draining the site of infection, eliciting a broadly protective immune response [71].

Chloroquine can also act on the immune system through cell signalling and regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Chloroquine is known to inhibit phosphorylation (activation) of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) in THP-1 cells as well as caspase-1 [72]. Activation of cells via MAPK signalling is frequently required by viruses to achieve their replication cycle [73]. In the model of HCoV-229 coronavirus, chloroquine-induced virus inhibition occurs through inhibition of p38 MAPK [44]. Chloroquine is a well-known immunomodulatory agent capable of mediating an anti-inflammatory response [11]. Therefore, there are clinical applications of this drug in inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis [74], [75], [76], lupus erythematosus [6,77] and sarcoidosis [78]. Chloroquine inhibits interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) mRNA expression in THP-1 cells and reduces IL-1β release [72]. Chloroquine-induced reduction of IL-1 and IL-6 cytokines was also found in monocytes/macrophages [79]. Chloroquine-induced inhibition of tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα) production by immune cells was reported to occur either through disruption of cellular iron metabolism [80], blockade of the conversion of pro-TNF into soluble mature TNFα molecules [81] and/or inhibition of TNFα mRNA expression [72,82,83]. Inhibition of the TNFα receptor was also reported in U937 monocytic cells treated with chloroquine [84]. In the Dengue virus model, chloroquine was found to inhibit interferon-alpha (IFNα), IFNβ, IFNγ, TNFα, IL-6 and IL-12 gene expression in U937 cells infected with Dengue-2 virus [33].

5. Conclusion

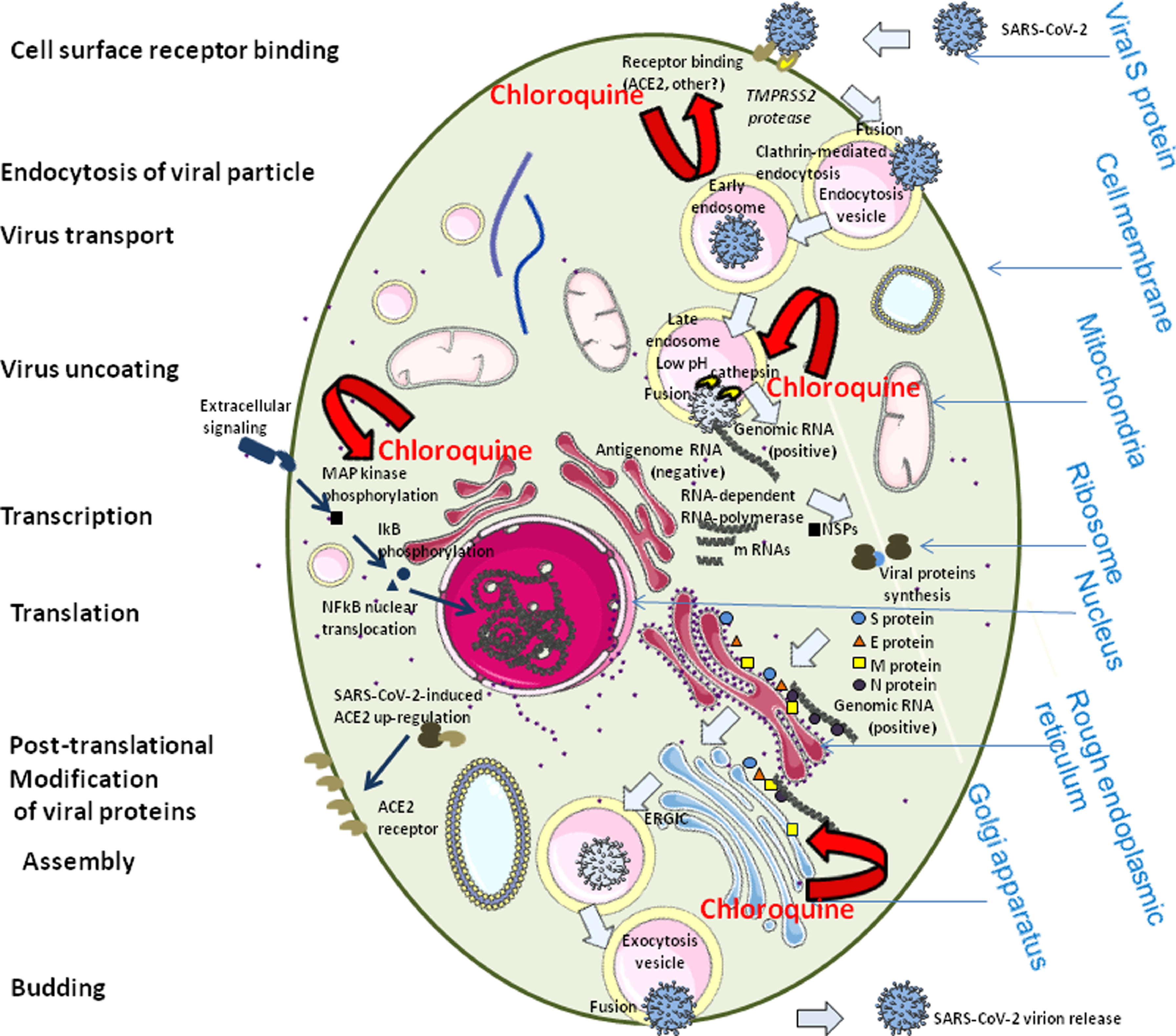

Chloroquine has been shown to be capable of inhibiting the in vitro replication of several coronaviruses. Recent publications support the hypothesis that chloroquine can improve the clinical outcome of patients infected by SARS-CoV-2. The multiple molecular mechanisms by which chloroquine can achieve such results remain to be further explored. Since SARS-CoV-2 was found a few days ago to utilise the same cell surface receptor ACE2 (expressed in lung, heart, kidney and intestine) as SARS-CoV-1 [85,86] (Table 1), it may be hypothesised that chloroquine also interferes with ACE2 receptor glycosylation thus preventing SARS-CoV-2 binding to target cells. Wang and Cheng reported that SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV upregulate the expression of ACE2 in lung tissue, a process that could accelerate their replication and spread [85]. Although the binding of SARS-CoV to sialic acids has not been reported so far (it is expected that Betacoronavirus adaptation to humans involves progressive loss of hemagglutinin-esterase lectin activity), if SARS-CoV-2 like other coronaviruses targets sialic acids on some cell subtypes, this interaction will be affected by chloroquine treatment [87,88]. Today, preliminary data indicate that chloroquine interferes with SARS-CoV-2 attempts to acidify the lysosomes and presumably inhibits cathepsins, which require a low pH for optimal cleavage of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein [89], a prerequisite to the formation of the autophagosome [49]. Obviously, it can be hypothesised that SARS-CoV-2 molecular crosstalk with its target cell can be altered by chloroquine through inhibition of kinases such as MAPK. Chloroquine could also interfere with proteolytic processing of the M protein and alter virion assembly and budding (Fig. 1). Finally, in COVID-19 disease this drug could act indirectly through reducing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and/or by activating anti-SARS-CoV-2 CD8+ T-cells.

Table 1. Human coronavirus (HCoV) receptors/co-receptors as possible targets for chloroquine-induced inhibition of the virus replication cycle

|

Coronavirus |

Receptora |

May also bind |

Replication cycle inhibited by chloroquine b |

|

Alphacoronavirus |

|||

|

HCoV-229E |

Aminopeptidase N (APN)/CD13 |

Yes |

|

|

HCoV-NL63 |

Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) |

? |

|

|

Heparan sulfate proteoglycans c |

|||

|

Betacoronavirus |

|||

|

HCoV-OC43 |

HLA class I d, IFN-inducible transmembrane (IFITM) proteins in endocytic vesicles e |

Sialic acid (O-acetylated sialic acid) f |

Yes |

|

SARS-CoV-1 |

Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) |

DC-SIGN/CD209, DC-SIGNr, DC-SIGN-related lectin LSECtin g |

Yes |

|

HCoV-HKU1 |

HLA class I h |

Sialic acid (O-acetylated sialic acid) |

? |

|

MERS-CoV i |

Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4)/CD26 |

Yes |

|

|

SARS-CoV-2 |

ACE2 i |

Sialic acid? |

Yes |

HLA, human leukocyte antigen.

a

Adapted from Graham et al. [91].

b

Chloroquine could interfere with receptor (ACE2) glycosylation and/or sialic acid biosynthesis.

c

According to Milewska et al. [92].

d

According to Collins [93].

e

According to Zhao et al. [94].

f

According to Vlasak et al. [95].

g

According to Huang et al. [96].

h

According to Chan et al. [97].

i

It is worth noting that different host cell proteases are required to activate the spike (S) protein for coronaviruses, such as SARS-CoV-1 S protein that requires activation by cathepsin L [89], or MERS-CoV that requires furin-mediated activation of the S protein [98].

Fig. 1. Schematic representation of the possible effects of chloroquine on the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) replication cycle. SARS-CoV2, like other human coronaviruses, harbours three envelope proteins, the spike (S) protein (180–220 kDa), the membrane (M) protein (25–35 kDa) and the envelope (E) protein (10–12 kDa), which are required for entry of infectious virions into target cells. The virion also contains the nucleocapsid (N), capable of binding to viral genomic RNA, and nsp3, a key component of the replicase complex. A subset of betacoronaviruses use a hemagglutinin-esterase (65 kDa) that binds sialic acids at the surface of glycoproteins. The S glycoprotein determines the host tropism. There is indication that SARS-CoV-2 binds to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) expressed on pneumocytes [85,99]. Binding to ACE2 is expected to trigger conformational changes in the S glycoprotein allowing cleavage by the transmembrane protease TMPRSS2 of the S protein and the release of S fragments into the cellular supernatant that inhibit virus neutralisation by antibodies [100]. The virus is then transported into the cell through the early and late endosomes where the host protease cathepsin L further cleaves the S protein at low pH, leading to fusion of the viral envelope and phospholipidic membrane of the endosomes resulting in release of the viral genome into the cell cytoplasm. Replication then starts and the positive-strand viral genomic RNA is transcribed into a negative RNA strand that is used as a template for the synthesis of viral mRNA. Synthesis of the negative RNA strand peaks earlier and falls faster than synthesis of the positive strand. Infected cells contain between 10 and 100 times more positive strands than negative strands. The ribosome machinery of the infected cells is diverted in favour of the virus, which then synthesises its non-structural proteins (NSPs) that assemble into the replicase-transcriptase complex to favour viral subgenomic mRNA synthesis (see the review by Fehr and Perlman for details [101]). Following replication, the envelope proteins are translated and inserted into the endoplasmic reticulum and then move to the Golgi compartment. Viral genomic RNA is packaged into the nucleocapsid and then envelope proteins are incorporated during the budding step to form mature virions. The M protein, which localises to the trans-Golgi network, plays an essential role during viral assembly by interacting with the other proteins of the virus. Following assembly, the newly formed viral particles are transported to the cell surface in vesicles and are released by exocytosis. It is possible that chloroquine interferes with ACE2 receptor glycosylation, thus preventing SARS-CoV-2 binding to target cells. Chloroquine could also possibly limit the biosynthesis of sialic acids that may be required for cell surface binding of SARS-CoV-2. If binding of some viral particles is achieved, chloroquine may modulate the acidification of endosomes thereby inhibiting formation of the autophagosome. Through reduction of cellular mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase activation, chloroquine may also inhibit virus replication. Moreover, chloroquine could alter M protein maturation and interfere with virion assembly and budding. With respect to the effect of chloroquine on the immune system, see the elegant review by Savarino et al. [11]. ERGIC, ER-Golgi intermediate compartment.

Already in 2007, some of us emphasised in this journal the possibility of using chloroquine to fight orphan viral infections [10]. The worldwide ongoing trials, including those involving the care of patients in our institute [90], will verify whether the hopes raised by chloroquine in the treatment of COVID-19 can be confirmed.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None declared.

Acknowledgment

The figure was designed using the Servier Medical Art supply of images available under a Creative Commons CC BY 3.0 license.

Funding: This study was supported by IHU–Méditerranée Infection, University of Marseille and CNRS (Marseille, France). This work has benefited from French state support, managed by the Agence nationale de la recherche (ANR), including the ‘Programme d'investissement d'avenir’ under the reference Méditerranée Infection 10-1AHU-03.

Ethical approval: Not required.

References

E.A. WinzelerMalaria research in the post-genomic era

Nature, 455 (2008), pp. 751-756

CrossRefView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

A.R. Parhizgar, A. TahghighiIntroducing new antimalarial analogues of chloroquine and amodiaquine: a narrative review

Iran J Med Sci, 42 (2017), pp. 115-128

View Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

editor

L.J. Bruce-Chwatt (Ed.), Chemotherapy of malaria (2nd ed.), WHO, Geneva, Switzerland (1981)

WHO Monograph Series 27

N.J. White, S. Pukrittayakamee, T.T. Hien, M.A. Faiz, O.A. Mokuolu, A.M. DondorpMalaria

Lancet, 383 (2014), pp. 723-735, 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60024-0

ArticleDownload PDFView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

T.E. Wellems, C.V. PloweChloroquine-resistant malaria

J Infect Dis, 184 (2001), pp. 770-776

View Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

S.J. Lee, E. Silverman, J.M. BargmanThe role of antimalarial agents in the treatment of SLE and lupus nephritis

Nat Rev Nephrol, 7 (2011), pp. 718-729, 10.1038/nrneph.2011.150

CrossRefView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

D. Raoult, M. Drancourt, G. VestrisBactericidal effect of doxycycline associated with lysosomotropic agents on Coxiella burnetii in P388D1 cells

Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 34 (1990), pp. 1512-1514, 10.1128/aac.34.8.1512

CrossRefView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

D. Raoult, P. Houpikian, D.H. Tissot, J.M. Riss, J. Arditi-Djiane, P. BrouquiTreatment of Q fever endocarditis: comparison of 2 regimens containing doxycycline and ofloxacin or hydroxychloroquine

Arch Intern Med, 159 (1999), pp. 167-173, 10.1001/archinte.159.2.167

View Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

A. Boulos, J.M. Rolain, D. RaoultAntibiotic susceptibility of Tropheryma whipplei in MRC5 cells

Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 48 (2004), pp. 747-752

View Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

J.M. Rolain, P. Colson, D. RaoultRecycling of chloroquine and its hydroxyl analogue to face bacterial, fungal and viral infection in the 21st century

Int J Antimicrob Agents, 30 (2007), pp. 297-308

ArticleDownload PDFView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

A. Savarino, J.R. Boelaert, A. Cassone, G. Majori, R. CaudaEffects of chloroquine on viral infections: an old drug against today's diseases?

Lancet Infect Dis, 3 (2003), pp. 722-727

ArticleDownload PDFView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

J.R. Boelaert, J. Piette, K. SperberThe potential place of chloroquine in the treatment of HIV-1-infected patients

J Clin Virol, 20 (2001), pp. 137-140

ArticleDownload PDFView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

C. Huang, Y. Wang, X. Li, L. Ren, J. Zhao, Y. Hu, et al.Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan

China. Lancet, 395 (2020), pp. 497-506, 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5

ArticleDownload PDFView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

N. Zhu, D. Zhang, W. Wang, X. Li, B. Yang, J. Song, et al.A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019

N Engl J Med, 382 (2020), pp. 727-733

CrossRefView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

P. Zhou, X.L. Yang, X.G. Wang, B. Hu, L. Zhang, W. Zhang, et al.Discovery of a novel coronavirus associated with the recent pneumonia outbreak in humans and its potential bat origin

bioRxiv (2020 Jan 23), 10.1101/2020.01.22.914952

H. Tsiang, F. SupertiAmmonium chloride and chloroquine inhibit rabies virus infection in neuroblastoma cells

Arch Virol, 81 (1984), pp. 377-382

View Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

P. Kronenberger, R. Vrijsen, A. BoeyéChloroquine induces empty capsid formation during poliovirus eclipse

J Virol, 65 (1991), pp. 7008-7011

CrossRefView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

W.P. Tsai, P.L. Nara, H.F. Kung, S. OroszlanInhibition of human immunodeficiency virus infectivity by chloroquine

AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses, 6 (1990), pp. 481-489, 10.1089/aid.1990.6.481

CrossRefView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

A. Savarino, L. Gennero, K. Sperber, J.R. BoelaertThe anti-HIV-1 activity of chloroquine

J Clin Virol, 20 (2001), pp. 131-135

ArticleDownload PDFView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

F. Romanelli, K.M. Smith, A.D. HovenChloroquine and hydroxychloroquine as inhibitors of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1) activity

Curr Pharm Des, 10 (2004), pp. 2643-2648

CrossRefView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

F. Superti, L. Seganti, W. Orsi, M. Divizia, R. Gabrieli, A. PanaThe effect of lipophilic amines on the growth of hepatitis A virus in Frp/3 cells

Arch Virol, 96 (1987), pp. 289-296, 10.1007/bf01320970

View Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

N.E. BishopPractical guidelines in antiviral therapy

Intervirology, 41 (1998), pp. 261-271

View Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

T. Mizui, S. Yamashina, I. Tanida, Y. Takei, T. Ueno, N. Sakamoto, et al.Inhibition of hepatitis C virus replication by chloroquine targeting virus-associated autophagy

J Gastroenterol, 45 (2010), pp. 195-203

CrossRefView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

D.K. Miller, J. LenardAntihistaminics, local anesthetics, and other amines as antiviral agents

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 78 (1981), pp. 3605-3609, 10.1073/pnas.78.6.3605

CrossRefView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

M. Shibata, H. Aoki, T. Tsurumi, Y. Sugiura, Y. Nishiyama, S. Suzuki, et al.Mechanism of uncoating of influenza B virus in MDCK cells: action of chloroquine

J Gen Virol, 64 (1983), pp. 1149-1156, 10.1099/0022-1317-64-5-1149

CrossRefView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

E.E. Ooi, J.S. Chew, J.P. Loh, R.C. ChuaIn vitro inhibition of human influenza A virus replication by chloroquine

Virol J, 3 (2006), p. 39

CrossRefView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

N.I. Paton, L. Lee, Y. Xu, E.E. Ooi, Y.B. Cheung, S. Archuleta, et al.Chloroquine for influenza prevention: a randomised, double-blind, placebo controlled trial

Lancet Infect Dis, 11 (2011), pp. 677-683

ArticleDownload PDFView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

Y. Yan, Z. Zou, Y. Sun, X. Li, K.F. Xu, Y. Wei, et al.Anti-malaria drug chloroquine is highly effective in treating avian influenza A H5N1 virus infection in an animal model

Cell Res, 23 (2013), pp. 300-302, 10.1038/cr.2012.165

CrossRefView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

X. De Lamballerie, V. Boisson, J.C. Reynier, S. Enault, R.N. Charrel, A. Flahault, et al.On Chikungunya acute infection and chloroquine treatment

Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis, 8 (2008), pp. 837-840, 10.1089/vbz.2008.0049

View Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

M. Khan, S.R. Santhosh, M. Tiwari, P.V. Lakshmana Rao, M. ParidaAssessment of in vitro prophylactic and therapeutic efficacy of chloroquine against Chikungunya virus in Vero cells

J Med Virol, 82 (2010), pp. 817-824

CrossRefView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

I. Delogu, X. de LamballerieChikungunya disease and chloroquine treatment

J Med Virol, 83 (2011), pp. 1058-1059

CrossRefView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

V.B. Randolph, G. Winkler, V. StollarAcidotropic amines inhibit proteolytic processing of flavivirus prM protein

Virology, 174 (1990), pp. 450-458, 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90099-d

ArticleDownload PDFView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

K.J. Farias, P.R. Machado, R.F. de Almeida Junior, A.A. de Aquino, B.A. da FonsecaChloroquine interferes with dengue-2 virus replication in U937 cells

Microbiol Immunol, 58 (2014), pp. 318-326

CrossRefView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

R. Delvecchio, L.M. Higa, P. Pezzuto, A.L. Valadao, P.P. Garcez, F.L. Monteiro, et al.Chloroquine, an endocytosis blocking agent, inhibits Zika virus infection in different cell models

Viruses, 8 (2016), p. E322, 10.3390/v8120322

S.E. Glushakova, I.S. LukashevichEarly events in arenavirus replication are sensitive to lysosomotropic compounds

Arch Virol, 104 (1989), pp. 157-161

View Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

M. Porotto, G. Orefice, C.C. Yokoyama, B.A. Mungall, R. Realubit, M.L. Sganga, et al.Simulating Henipavirus multicycle replication in a screening assay leads to identification of a promising candidate for therapy

J Virol, 83 (2009), pp. 5148-5155

CrossRefView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

A.N. Freiberg, M.N. Worthy, B. Lee, M.R. HolbrookCombined chloroquine and ribavirin treatment does not prevent death in a hamster model of Nipah and Hendra virus infection

J Gen Virol, 91 (2010), pp. 765-772, 10.1099/vir.0.017269-0

CrossRefView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

O. Ferraris, M. Moroso, O. Pernet, S. Emonet, A. Ferrier Rembert, G. Paranhos-Baccala, et al.Evaluation of Crimean–Congo hemorrhagic fever virus in vitro inhibition by chloroquine and chlorpromazine, two FDA approved molecules

Antiviral Res, 118 (2015), pp. 75-81, 10.1016/j.antiviral.2015.03.005

ArticleDownload PDFView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

S.D. Dowall, A. Bosworth, R. Watson, K. Bewley, I. Taylor, E. Rayner, et al.Chloroquine inhibited Ebola virus replication in vitro but failed to protect against infection and disease in the in vivo guinea pig model

J Gen Virol, 96 (2015), pp. 3484-3492

CrossRefView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

E.A. Kouroumalis, J. KoskinasTreatment of chronic active hepatitis B (CAH B) with chloroquine: a preliminary report

Ann Acad Med Singapore, 15 (1986), pp. 149-152

View Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

A.H. Koyama, T. UchidaInhibition of multiplication of herpes simplex virus type 1 by ammonium chloride and chloroquine

Virology, 138 (1984), pp. 332-335

ArticleDownload PDFView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

E. Keyaerts, S. Li, L. Vijgen, E. Rysman, J. Verbeeck, M. Van Ranst, et al.Antiviral activity of chloroquine against human coronavirus OC43 infection in newborn mice

Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 53 (2009), pp. 3416-3421

CrossRefView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

D. Blau, K. HolmesHuman coronavirus HCoV-229E enters susceptible cells via the endocytic pathway

E. Lavi, S.R. Weiss, S.T. Hingley (Eds.), The nidoviruses (coronaviruses and arteriviruses), Kluwer, New York, NY (2001), pp. 193-197

CrossRefView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

M. Kono, K. Tatsumi, A.M. Imai, K. Saito, T. Kuriyama, H. ShirasawaInhibition of human coronavirus 229E infection in human epithelial lung cells (L132) by chloroquine: involvement of p38 MAPK and ERK

Antiviral Res, 77 (2008), pp. 150-152, 10.1016/j.antiviral.2007.10.011

ArticleDownload PDFView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

L. Shen, Y. Yang, F. Ye, G. Liu, M. Desforges, P.J. Talbot, et al.Safe and sensitive antiviral screening platform based on recombinant human coronavirus OC43 expressing the luciferase reporter gene

Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 60 (2016), pp. 5492-5503, 10.1128/AAC.00814-16

View Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

A.H. de Wilde, D. Jochmans, C.C. Posthuma, J.C. Zevenhoven-Dobbe, S. van Nieuwkoop, T.M. Bestebroer, et al.Screening of an FDA-approved compound library identifies four small-molecule inhibitors of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus replication in cell culture

Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 58 (2014), pp. 4875-4884, 10.1128/AAC.03011-14

View Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

Y. Mo, D. FisherA review of treatment modalities for Middle East respiratory syndrome

J Antimicrob Chemother, 71 (2016), pp. 3340-3350

CrossRefView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

C. Burkard, M.H. Verheije, O. Wicht, S.I. van Kasteren, F.J. van Kuppeveld, B.L. Haagmans, et al.Coronavirus cell entry occurs through the endo-/lysosomal pathway in a proteolysis-dependent manner

PLoS Pathog, 10 (2014), Article e1004502

M. Wang, R. Cao, L. Zhang, X. Yang, J. Liu, M. Xu, et al.Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro

Cell Res, 30 (2020), pp. 269-271, 10.1038/s41422-020-0282-0

CrossRefView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

J. Gao, Z. Tian, X. YangBreakthrough: chloroquine phosphate has shown apparent efficacy in treatment of COVID-19 associated pneumonia in clinical studies

Biosci Trends (2020 Feb), 10.5582/bst.2020.01047

[Epub ahead of print]

Multicenter Collaboration Group of Department of Science and Technology of Guangdong Province and Health Commission of Guangdong Province for chloroquine in the treatment of novel coronavirus pneumoniaExpert consensus on chloroquine phosphate for the treatment of novel coronavirus pneumonia [in Chinese]

Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi, 43 (2020), p. E019, 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1001-0939.2020.0019

H.N. BernsteinOcular safety of hydroxychloroquine

Ann Ophthalmol, 23 (1991), pp. 292-296

View Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

N.B. Ratliff, M.L. Estes, J.L. Myles, E.K. Shirey, J.T. McMahonDiagnosis of chloroquine cardiomyopathy by endomyocardial biopsy

N Engl J Med, 316 (1987), pp. 191-193

CrossRefView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

G.J. Cubero, J.J. Rodriguez Reguero, J.M. Rojo OrtegaRestrictive cardiomyopathy caused by chloroquine

Br Heart J, 69 (1993), pp. 451-452

C. HarrisonCoronavirus puts drug repurposing on the fast track

Nature Biotechnology (2020 Feb 27), 10.1038/d41587-020-00003-1

J.J. Kwiek, T.A. Haystead, J. RudolphKinetic mechanism of quinone oxidoreductase 2 and its inhibition by the antimalarial quinolines

Biochemistry, 43 (2004), pp. 4538-4547

View Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

A. VarkiSialic acids as ligands in recognition phenomena

FASEB J, 11 (1997), pp. 248-255

CrossRefView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

S. Olofsson, U. Kumlin, K. Dimock, N. ArnbergAvian influenza and sialic acid receptors: more than meets the eye?

Lancet Infect Dis, 5 (2005), pp. 184-188

ArticleDownload PDFView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

M.J. Vincent, E. Bergeron, S. Benjannet, B.R. Erickson, P.E. Rollin, T.G. Ksiazek, et al.Chloroquine is a potent inhibitor of SARS coronavirus infection and spread

Virol J, 2 (2005), p. 69, 10.1186/1743-422X-2-69

V. Tricou, N.N. Minh, T.P. Van, S.J. Lee, J. Farrar, B. Wills, et al.A randomized controlled trial of chloroquine for the treatment of dengue in Vietnamese adults

PLoS Negl Trop Dis, 4 (2010), p. e785, 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000785

B. Gay, E. Bernard, M. Solignat, N. Chazal, C. Devaux, L. BriantpH-dependent entry of Chikungunya virus into Aedes albopictus cells

Infect Genet Evol, 12 (2012), pp. 1275-1281, 10.1016/j.meegid.2012.02.003

ArticleDownload PDFView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

Z.Y. Yang, Y. Huang, L. Ganesh, K. Leung, W.P. Kong, O. Schwartz, et al.pH-dependent entry of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus is mediated by the spike glycoprotein and enhanced by dendritic cell transfer through DC-SIGN

J Virol, 78 (2004), pp. 5642-5650, 10.1128/JVI.78.11.5642-5650.2004

View Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

H. Wang, P. Yang, K. Liu, F. Guo, Y. Zhang, G. Zhang, et al.SARS coronavirus entry into host cells through a novel clathrin- and caveolae-independent endocytic pathway

Cell Res, 18 (2008), pp. 290-301, 10.1038/cr.2008.15

CrossRefView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

S. Cassell, J. Edwards, D.T. BrownEffects of lysosomotropic weak bases on infection of BHK-21 cells by Sindbis virus

J Virol, 52 (1984), pp. 857-864

CrossRefView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

A. Savarino, M.B. Lucia, E. Rastrelli, S. Rutella, C. Golotta, E. Morra, et al.Anti-HIV effects of chloroquine: inhibition of viral particle glycosylation and synergism with protease inhibitors

J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 35 (1996), pp. 223-232

C.A. Harley, A. Dasgupta, D.W. WilsonCharacterization of herpes simplex virus-containing organelles by subcellular fractionation: role for organelle acidification in assembly of infectious particles

J Virol, 75 (2001), pp. 1236-1251

View Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

J. Klumperman, J.K. Locker, A. Meijer, M.C. Horzinek, H.J. Geuze, P.J. RottierCoronavirus M proteins accumulate in the Golgi complex beyond the site of virion budding

J Virol, 68 (1994), pp. 6523-6534

CrossRefView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

A. Perrier, A. Bonnin, L. Desmarets, A. Danneels, A. Goffard, Y. Rouillé, et al.The C-terminal domain of the MERS coronavirus M protein contains a trans-Golgi network localization signal

J Biol Chem, 294 (2019), pp. 14406-14421

CrossRefView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

S.S. Diebold, T. Kaisho, H. Hemmi, S. Akira, C. Reis e SousaInnate antiviral responses by means of TLR7-mediated recognition of single-stranded RNA

Science, 303 (2004), pp. 1529-1531

CrossRefView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

D. Accapezzato, V. Visco, V. Francavilla, C. Molette, T. Donato, M. Paroli, et al.Chloroquine enhances human CD8+ T cell responses against soluble antigens in vivo

J Exp Med, 202 (2005), pp. 817-828

CrossRefView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

B. Garulli, G. Di Mario, E. Sciaraffia, D. Accapezzato, V. Barnaba, M.R. CastrucciEnhancement of T cell-mediated immune responses to whole inactivated influenza virus by chloroquine treatment in vivo

Vaccine, 31 (2013), pp. 1717-1724, 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.01.037

ArticleDownload PDFView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

M. Steiz, J. Valbracht, J. Quach, M. LotzGold sodium thiomalate and chloroquine inhibit cytokine production in monocytic THP-1 cells through distinct transcriptional and posttranslational mechanisms

J Clin Immunol, 23 (2003), pp. 477-484

doi: 10.1023/B:JOCI.0000010424.41475.17

L. Briant, V. Robert-Hebmann, C. Acquaviva, A. Pelchen-Matthews, M. Marsh, C. DevauxThe protein tyrosine kinase p56lck is required for triggering NF-κB activation upon interaction of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein gp120 with cell surface CD4

J Virol, 72 (1998), pp. 6207-6214

CrossRefView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

H. Fuld, L. HorwichTreatment of rheumatoid arthritis with chloroquine

Br Med J, 15 (1958), pp. 1199-1201, 10.1136/bmj.2.5106.1199

CrossRefView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

A.H. MackenzieAntimalarial drugs for rheumatoid arthritis

Am J Med, 75 (1983), pp. 48-58

ArticleDownload PDFView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

T.S. Sharma, E.J. Do, M.C.M. WaskoAnti-malarials: are there benefits beyond mild disease?

Curr Treat Options Rheumatol, 2 (2016), pp. 1-12, 10.1007/s40674-016-0036-9

CrossRefView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

A. Wozniacka, A. Lesiak, J. Narbutt, D.P. McCauliffe, A. Sysa-JedrzejowskaChloroquine treatment influences proinflammatory cytokine levels in systemic lupus erythematosus patients

Lupus, 15 (2006), pp. 268-275

CrossRefView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

O.P. SharmaEffectiveness of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in treating selected patients with sarcoidosis with neurological involvement

Arch Neurol, 55 (1998), pp. 1248-1254

View Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

C.H. Jang, J.H. Choi, M.S. Byun, D.M. JueChloroquine inhibits production of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 from lipopolysaccharide-stimulated human monocytes/macrophages by different modes

Rheumatology, 45 (2006), pp. 703-710

CrossRefView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

S. Picot, F. Peyron, A. Donadille, J.-P. Vuillez, G. Barbe, P. Ambroise-ThomasChloroquine-induced inhibition of the production of TNF, but not of IL-6, is affected by disruption of iron metabolism

Immunology, 80 (1993), pp. 127-133

View Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

J.Y. Jeong, D.M. JueChloroquine inhibits processing of tumor necrosis factor in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages

J Immunol, 158 (1997), pp. 4901-4907

View Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

X. Zhu, W. Ertel, A. Ayala, M.H. Morrison, M.M. Perrin, I.H. ChaudryChloroquine inhibits macrophage tumour necrosis factor-α mRNA transcription

Immunology, 80 (1993), pp. 122-126

View Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

S.M. Weber, S.M. LevitzChloroquine interferes with lipopolysaccharide-induced TNF-α gene expression by a nonlysosomotropic mechanism

J Immunol, 165 (2000), pp. 1534-1540, 10.4049/jimmunol.165.3.1534

CrossRefView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

J.Y. Jeong, J.W. Choi, K.I. Jeon, D.M. JueChloroquine decreases cell-surface expression of tumour necrosis factor receptors in human histiocytic U-937 cells

Immunology, 105 (2002), pp. 83-91, 10.1046/j.0019-2805.2001.01339.x

View Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

P.H. Wang, Y. ChengIncreasing host cellular receptor—angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) expression by coronavirus may facilitate 2019-nCoV infection

bioRxiv (2020 Feb 27), 10.1101/2020.02.24.963348

R. Li, S. Qiao, G. ZhangAnalysis of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) from different species sheds some light on cross-species receptor usage of a novel coronavirus 2019-nCoV

J Infect (2020 Feb 21), 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.02.013

[Epub ahead of print]

Q. Zeng, M.A. Langereis, A.L.W. van Vliet, E.G. Huizinga, R.J. de GrootStructure of coronavirus hemagglutinin-esterase offers insight into corona and influenza virus evolution

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 105 (2008), pp. 9065-9069

CrossRefView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

M.J.G. Bakkers, Y. Lang, L.J. Feistsma, R.J.G. Hulswit, S.A.H. de Poot, A.L.W. van Vliet, et al.Betacoronavirus adaptation to humans involved progressive loss of hemagglutinin-esterase lectin activity

Cell Host Microbe, 21 (2017), pp. 356-366, 10.1016/j.chom.2017.02.008

ArticleDownload PDFView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

G. Simmons, S. Bertram, I. Glowacka, I. Steffen, C. Chaipan, J. Agudelo, et al.Different host cell proteases activate the SARS-coronavirus spike-protein for cell–cell and virus–cell fusion

Virology, 413 (2011), pp. 265-274, 10.1016/j.virol.2011.02.020

ArticleDownload PDFView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

P. Colson, J.M. Rolain, J.C. Lagier, P. Brouqui, D. RaoultChloroquine and hydroxychloroquine as available weapons to fight COVID-19

Int J Antimicrob Agents (2020 Mar 4), Article 105932, 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105932

ArticleDownload PDFGoogle Scholar

R.L. Graham, E.F. Donaldson, R.S. BaricA decade after SARS: strategies to control emerging coronaviruses

Nat Rev Microbiol, 11 (2013), pp. 836-848

CrossRefView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

A. Milewska, M. Zarebski, P. Nowak, K. Stozek, J. Potempa, K. PyrcHuman coronavirus NL63 utilizes heparan sulfate proteoglycans for attachment to target cells

J Virol, 88 (2014), pp. 13221-13230

View Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

A.R. CollinsHLA class I antigen serves as a receptor for human coronavirus OC43

Immunol Invest, 22 (1993), pp. 95-103

CrossRefView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

X. Zhao, F. Guo, F. Liu, A. Cuconati, J. Chang, T.M. Block, et al.Interferon induction of IFITM proteins promotes infection by human coronavirus OC43

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 111 (2014), pp. 6756-6761

CrossRefView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

R. Vlasak, W. Luytjes, W. Spaan, P. PaleseHuman and bovine coronaviruses recognize sialic acid-containing receptors similar to those of influenza C viruses

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 85 (1988), pp. 4526-4529

CrossRefView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

X. Huang, W. Dong, A. Milewska, A. Golda, Y. Qi, Q.K. Zhu, et al.Human coronavirus HKU1 spike protein uses O-acetylated sialic acid as an attachment receptor determinant and employs hemagglutinin-esterase protein as a receptor-destroying enzyme

J Virol, 89 (2015), pp. 7202-7213

View Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

C.M. Chan, S.K.P. Lau, P.C.Y. Woo, H. Tse, B.J. Zheng, L. Chen, et al.Identification of major histocompatibility complex class I C molecule as an attachment factor that facilitates coronavirus HKU1 spike-mediated infection

J Virol, 83 (2009), pp. 1026-1035

CrossRefView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

J.K. Millet, G.R. WhittakerHost cell entry of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus after two-step, furin-mediated activation of the spike protein

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 111 (2014), pp. 15214-15219

Q.

Does chloroquine provide us with hope for treatment of COVID-19 and is there precedent that chloroquine can treat viruses.

A.

Yes, there is hope.

Chloroquine, a widely-used anti-malarial and autoimmune disease drug, is a form of Quinine that was made in Germany by Bayer in 1934. The drug has a long history of use and is available. Chloroquine is known to block virus infection by decreasing the acidity (or increasing the pH) required for virus to fuse with the a cell, as well as interfering with cellular receptors of SARS-CoVAs (Note: COVID19 or coronavirus (2019-nCoV), is officially referred to in medical journals as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 or SARS-CoV-2).

As reported by Christian Devaux on March 12, 2020 in the International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents, chloroquine possesses antiviral activity in laboratories against viruses as diverse as rabies, poliovirus, hepatitis A virus, influenza A and B viruses, influenza A H5N1 virus, Dengue virus, Zika virus, and others. The antiviral properties of chloroquine described in the laboratory have sometimes been confirmed during treatment of virus-infected patients but have not always been reproduced in clinical trials depending on the disease.

A recent paper by Dr. Manli Wang and Gengfu Xiao published in Cell Research reported that both chloroquine and the antiviral drug remdesivir inhibited SARS-CoV-2 in the laboratory and moved to assess these drugs in patients suffering from COVID-19.

According to a recent report by Dr. Gao published in Bioscience Trends approximately 100 infected Chinese patients treated with chloroquine experienced a more rapid decline in fever and improvement of lung computed tomography (CT) images and required a shorter time to recover compared with control groups, with no obvious serious adverse effects.

Yesterday anecdotal information was shared by a woman whose husband’s infection with SARS-CoV-2 was greatly improved as a result of drug treatment.

More information can be found below.

New insights on the antiviral effects of chloroquine against coronavirus: what to expect for COVID-19?

Christian A.DevauxabcJean-MarcRolainacPhilippeColsonacDidierRaoultac

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105938Get rights and content

International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents

Abstract

Recently, a novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV), officially known as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), emerged in China. Despite drastic containment measures, the spread of this virus is ongoing. SARS-CoV-2 is the aetiological agent of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) characterised by pulmonary infection in humans. The efforts of international health authorities have since focused on rapid diagnosis and isolation of patients as well as the search for therapies able to counter the most severe effects of the disease. In the absence of a known efficient therapy and because of the situation of a public-health emergency, it made sense to investigate the possible effect of chloroquine/hydroxychloroquine against SARS-CoV-2 since this molecule was previously described as a potent inhibitor of most coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-1. Preliminary trials of chloroquine repurposing in the treatment of COVID-19 in China have been encouraging, leading to several new trials. Here we discuss the possible mechanisms of chloroquine interference with the SARS-CoV-2 replication cycle.

1. Introduction

Chloroquine is an amine acidotropic form of quinine that was synthesised in Germany by Bayer in 1934 and emerged approximately 70 years ago as an effective substitute for natural quinine [1,2]. Quinine is a compound found in the bark of Cinchona trees native to Peru and was the previous drug of choice against malaria [3]. For decades, chloroquine was a front-line drug for the treatment and prophylaxis of malaria and is one of the most prescribed drugs worldwide [4]. Chloroquine and the 4-aminoquinoline drug hydroxychloroquine belong to the same molecular family. Hydroxychloroquine differs from chloroquine by the presence of a hydroxyl group at the end of the side chain: the N-ethyl substituent is β-hydroxylated. This molecule is available for oral administration in the form of hydroxychloroquine sulfate. Hydroxychloroquine has pharmacokinetics similar to that of chloroquine, with rapid gastrointestinal absorption and renal elimination. However, the clinical indications and toxic doses of these drugs slightly differ. In malaria, the indication for chloroquine was a high dose for a short period of time (due to its toxicity at high doses) or a low dose for a long period of time. Hydroxychloroquine was reported to be as active as chloroquine against Plasmodium falciparum malaria and less toxic, but it is much less active than chloroquine against chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum owing to its physicochemical properties. What is advantageous with hydroxychloroquine is that it can be used in high doses for long periods with very good tolerance. Unfortunately, the efficacy of chloroquine gradually declined due to the continuous emergence of chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum strains [5]. Chloroquine is also utilised in the treatment of autoimmune diseases [6]. Yet the activity of the molecule is not limited to malaria and the control of inflammatory processes, as illustrated by its broad-spectrum activity against a range of bacterial, fungal and viral infections [7], [8], [9], [10]. Indeed, in the mid-1990s, due to its tolerability, rare toxicity reports, inexpensive cost and immunomodulatory properties [11], chloroquine repurposing was explored against human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and other viruses associated with inflammation and was found to be efficient in inhibiting their replication cycle [12].

Recently, a novel coronavirus emerged in the Chinese city of Wuhan in December 2019. After human coronavirus 229E (HCoV-229E) (classified in the genus Alphacoronavirus) and HCoV-OC43 (Betacoronavirus lineage 2a member) described in the 1960s, SARS-CoV-1 (Betacoronavirus lineage 2b member) that emerged in March 2003, HCoV-NL63 (Alphacoronavirus lineage 1b member) described in 2004, HCoV-HKU1 (Betacoronavirus lineage 2a member) discovered in 2005, and finally MERS-CoV that emerged in 2012 (classified in Betacoronavirus lineage 2c), the novel coronavirus is the seventh human coronavirus described to date as being responsible for respiratory infection. Evidence was rapidly reported that patients were suffering from an infection with a novel Betacoronavirus tentatively named 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) [13,14]. Despite drastic containment measures, the spread of 2019-nCoV, now officially known as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), is ongoing. Phylogenetic analysis of this virus indicated that it is different (∼80% nucleotide identity) but related to SARS-CoV-1 [15]. Because the world is threatened by the possibility of a SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, the broad-spectrum antiviral effects of chloroquine warranted particular attention for repurposing this drug in the therapy of the disease caused by SARS-CoV-2, named coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

2. Antiviral properties of chloroquine

In vitro, chloroquine appears as a versatile bioactive agent reported to possess antiviral activity against RNA viruses as diverse as rabies virus [16], poliovirus [17], HIV [12,[18], [19], [20]], hepatitis A virus [21,22], hepatitis C virus [23], influenza A and B viruses [24], [25], [26], [27], influenza A H5N1 virus [28], Chikungunya virus [29], [30], [31], Dengue virus [32,33], Zika virus [34], Lassa virus [35], Hendra and Nipah viruses [36,37], Crimean–Congo hemorrhagic fever virus [38] and Ebola virus [39], as well as various DNA viruses such as hepatitis B virus [40] and herpes simplex virus [41].The antiviral properties of chloroquine described in vitro have sometimes been confirmed during treatment of virus-infected patients but have not always been reproduced in clinical trials depending on the disease, the concentration of chloroquine used, the duration of treatment and the clinical team in charge of the trial.

Regarding coronaviruses, the potential therapeutic benefits of chloroquine were notably reported for SARS-CoV-1 [11,42]. Chloroquine was also reported to inhibit in vitro the replication of HCoV-229E in epithelial lung cell cultures [43,44]. In 2009, it was reported that lethal infections of newborn mice with the HCoV-O43 coronavirus could be averted by administering chloroquine through the mother's milk. In vitro experiments also showed a strong antiviral effect of chloroquine on a recombinant HCoV-O43 coronavirus [45]. Although chloroquine was reported to be active against Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in vitro [46], this observation remains controversial [47].

3. Potential antiviral effect of chloroquine against SARS-CoV-2

Because of its broad spectrum of action against viruses, including most coronaviruses and particularly its close relative SARS-CoV-1, and because coronavirus cell entry occurs through the endolysosomal pathway [48], it made sense in a situation of a public-health emergency and the absence of any known efficient therapy to investigate the possible effect of chloroquine against SARS-CoV-2. A recent paper reported that both chloroquine and the antiviral drug remdesivir inhibited SARS-CoV-2 in vitro and suggested these drugs be assessed in human patients suffering from COVID-19 [49].

Recently, the China National Center for Biotechnology Development indicated that chloroquine is one of the three drugs with a promising profile against the new SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus that causes COVID-19. Chloroquine repurposing was investigated in hospitals in Beijing, in central China's Hunan Province and South China's Guangdong Province. According to preliminary reports [50,51] from the Chinese authorities suggesting that approximately 100 infected patients treated with chloroquine experienced a more rapid decline in fever and improvement of lung computed tomography (CT) images and required a shorter time to recover compared with control groups, with no obvious serious adverse effects, the Chinese medical advisory board has suggested chloroquine inclusion in the SARS-CoV-2 treatment guidelines. As a result, chloroquine is probably the first molecule to be used in China and abroad on the front line for the treatment of severe SARS-CoV-2 infections. Although the long use of this drug in malaria therapy demonstrates the safety of acute chloroquine administration to humans, one cannot ignore the minor risk of macular retinopathy, which depends on the cumulative dose [52], and the existence of some reports on cardiomyopathy as a severe adverse effect caused by chloroquine [53,54]. A survey of SARS-CoV-2-infected patients for adverse effects of chloroquine therapy remains to be performed. However, chloroquine is currently among the best available candidates to impact the severity of SARS-CoV-2 infections in humans. Currently, at least ten clinical trials are testing chloroquine as an anti-COVID-19 therapy [55].

4. Mode of action of chloroquine

Chloroquine has multiple mechanisms of action that may differ according to the pathogen studied.

Chloroquine can inhibit a pre-entry step of the viral cycle by interfering with viral particles binding to their cellular cell surface receptor. Chloroquine was shown to inhibit quinone reductase 2 [56], a structural neighbour of UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 2-epimerases [57] that are involved in the biosynthesis of sialic acids. The sialic acids are acidic monosaccharides found at the extremity of sugar chains present on cell transmembrane proteins and are critical components of ligand recognition. The possible interference of chloroquine with sialic acid biosynthesis could account for the broad antiviral spectrum of that drug since viruses such as the human coronavirus HCoV-O43 and the orthomyxoviruses use sialic acid moieties as receptors [58]. The potent anti-SARS-CoV-1 effects of chloroquine in vitro were considered attributable to a deficit in the glycosylation of a virus cell surface receptor, the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) on Vero cells [59].

Chloroquine can also impair another early stage of virus replication by interfering with the pH-dependent endosome-mediated viral entry of enveloped viruses such as Dengue virus or Chikungunya virus [60,61]. Due to the alkalisation of endosomes, chloroquine was an effective in vitro treatment against Chikungunya virus when added to Vero cells prior to virus exposure [30]. The mechanism of inhibition likely involved the prevention of endocytosis and/or rapid elevation of the endosomal pH and abrogation of virus–endosome fusion. A pH-dependant mechanism of entry of coronavirus into target cells was also reported for SARS-CoV-1 after binding of the DC-SIGN receptor [62]. The activation step that occurs in endosomes at acidic pH results in fusion of the viral and endosomal membranes leading to the release of the viral SARS-CoV-1 genome into the cytosol [63]. In the absence of antiviral drug, the virus is targeted to the lysosomal compartment where the low pH, along with the action of enzymes, disrupts the viral particle, thus liberating the infectious nucleic acid and, in several cases, enzymes necessary for its replication [64]. Chloroquine-mediated inhibition of hepatitis A virus was found to be associated with uncoating, thus blocking its entire replication cycle [22].

Chloroquine can also interfere with the post-translational modification of viral proteins. These post-translational modifications, which involve proteases and glycosyltransferases, occur within the endoplasmic reticulum or the trans-Golgi network vesicles and may require a low pH. For HIV, the antiretroviral effect of chloroquine is attributable to a post-transcriptional inhibition of glycosylation of the gp120 envelope glycoprotein, and the neosynthesised virus particles are non-infectious [19,65]. Chloroquine also inhibits the replication Dengue-2 virus by affecting the normal proteolytic processing of the flavivirus prM protein to M protein [32]. As a result, viral infectivity is impaired. In the herpes simplex virus (HSV) model, chloroquine inhibited budding with accumulation of non-infectious HSV-1 particles in the trans-Golgi network [66]. Using non-human coronavirus, it was shown that the intracellular site of coronavirus budding is determined by the localisation of its membrane M proteins that accumulate in the Golgi complex beyond the site of virion budding [67], suggesting a possible action of chloroquine on SARS-CoV-2 at this step of the replication cycle. It was recently reported that the C-terminal domain of the MERS-CoV M protein contains a trans-Golgi network localisation signal [68].

Beside affecting the virus maturation process, pH modulation by chloroquine can impair the proper maturation of viral protein [32] and the recognition of viral antigen by dendritic cells, which occurs through a Toll-like receptor-dependent pathway that requires endosomal acidification [69]. On the contrary, other proposed effects of chloroquine on the immune system include increasing the export of soluble antigens into the cytosol of dendritic cells and the enhancement of human cytotoxic CD8+ T-cell responses against viral antigens [70]. In the influenza virus model, it was reported that chloroquine improve the cross-presentation of non-replicating virus antigen by dendritic cells to CD8+ T-cells recruited to lymph nodes draining the site of infection, eliciting a broadly protective immune response [71].

Chloroquine can also act on the immune system through cell signalling and regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Chloroquine is known to inhibit phosphorylation (activation) of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) in THP-1 cells as well as caspase-1 [72]. Activation of cells via MAPK signalling is frequently required by viruses to achieve their replication cycle [73]. In the model of HCoV-229 coronavirus, chloroquine-induced virus inhibition occurs through inhibition of p38 MAPK [44]. Chloroquine is a well-known immunomodulatory agent capable of mediating an anti-inflammatory response [11]. Therefore, there are clinical applications of this drug in inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis [74], [75], [76], lupus erythematosus [6,77] and sarcoidosis [78]. Chloroquine inhibits interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) mRNA expression in THP-1 cells and reduces IL-1β release [72]. Chloroquine-induced reduction of IL-1 and IL-6 cytokines was also found in monocytes/macrophages [79]. Chloroquine-induced inhibition of tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα) production by immune cells was reported to occur either through disruption of cellular iron metabolism [80], blockade of the conversion of pro-TNF into soluble mature TNFα molecules [81] and/or inhibition of TNFα mRNA expression [72,82,83]. Inhibition of the TNFα receptor was also reported in U937 monocytic cells treated with chloroquine [84]. In the Dengue virus model, chloroquine was found to inhibit interferon-alpha (IFNα), IFNβ, IFNγ, TNFα, IL-6 and IL-12 gene expression in U937 cells infected with Dengue-2 virus [33].

5. Conclusion

Chloroquine has been shown to be capable of inhibiting the in vitro replication of several coronaviruses. Recent publications support the hypothesis that chloroquine can improve the clinical outcome of patients infected by SARS-CoV-2. The multiple molecular mechanisms by which chloroquine can achieve such results remain to be further explored. Since SARS-CoV-2 was found a few days ago to utilise the same cell surface receptor ACE2 (expressed in lung, heart, kidney and intestine) as SARS-CoV-1 [85,86] (Table 1), it may be hypothesised that chloroquine also interferes with ACE2 receptor glycosylation thus preventing SARS-CoV-2 binding to target cells. Wang and Cheng reported that SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV upregulate the expression of ACE2 in lung tissue, a process that could accelerate their replication and spread [85]. Although the binding of SARS-CoV to sialic acids has not been reported so far (it is expected that Betacoronavirus adaptation to humans involves progressive loss of hemagglutinin-esterase lectin activity), if SARS-CoV-2 like other coronaviruses targets sialic acids on some cell subtypes, this interaction will be affected by chloroquine treatment [87,88]. Today, preliminary data indicate that chloroquine interferes with SARS-CoV-2 attempts to acidify the lysosomes and presumably inhibits cathepsins, which require a low pH for optimal cleavage of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein [89], a prerequisite to the formation of the autophagosome [49]. Obviously, it can be hypothesised that SARS-CoV-2 molecular crosstalk with its target cell can be altered by chloroquine through inhibition of kinases such as MAPK. Chloroquine could also interfere with proteolytic processing of the M protein and alter virion assembly and budding (Fig. 1). Finally, in COVID-19 disease this drug could act indirectly through reducing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and/or by activating anti-SARS-CoV-2 CD8+ T-cells.

Table 1. Human coronavirus (HCoV) receptors/co-receptors as possible targets for chloroquine-induced inhibition of the virus replication cycle

|

Coronavirus |

Receptora |

May also bind |

Replication cycle inhibited by chloroquine b |

|

Alphacoronavirus |

|||

|

HCoV-229E |

Aminopeptidase N (APN)/CD13 |

Yes |

|

|

HCoV-NL63 |

Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) |

? |

|

|

Heparan sulfate proteoglycans c |

|||

|

Betacoronavirus |

|||

|

HCoV-OC43 |

HLA class I d, IFN-inducible transmembrane (IFITM) proteins in endocytic vesicles e |

Sialic acid (O-acetylated sialic acid) f |

Yes |

|

SARS-CoV-1 |

Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) |

DC-SIGN/CD209, DC-SIGNr, DC-SIGN-related lectin LSECtin g |

Yes |

|

HCoV-HKU1 |

HLA class I h |

Sialic acid (O-acetylated sialic acid) |

? |

|

MERS-CoV i |

Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4)/CD26 |

Yes |

|

|

SARS-CoV-2 |

ACE2 i |

Sialic acid? |

Yes |

HLA, human leukocyte antigen.

a

Adapted from Graham et al. [91].

b

Chloroquine could interfere with receptor (ACE2) glycosylation and/or sialic acid biosynthesis.

c

According to Milewska et al. [92].

d

According to Collins [93].

e

According to Zhao et al. [94].

f

According to Vlasak et al. [95].

g

According to Huang et al. [96].

h

According to Chan et al. [97].

i

It is worth noting that different host cell proteases are required to activate the spike (S) protein for coronaviruses, such as SARS-CoV-1 S protein that requires activation by cathepsin L [89], or MERS-CoV that requires furin-mediated activation of the S protein [98].

https://www.medexpert.com/images/1-s2.0-S0924857920300881-gr1_lrg.jpg

Fig. 1. Schematic representation of the possible effects of chloroquine on the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) replication cycle. SARS-CoV2, like other human coronaviruses, harbours three envelope proteins, the spike (S) protein (180–220 kDa), the membrane (M) protein (25–35 kDa) and the envelope (E) protein (10–12 kDa), which are required for entry of infectious virions into target cells. The virion also contains the nucleocapsid (N), capable of binding to viral genomic RNA, and nsp3, a key component of the replicase complex. A subset of betacoronaviruses use a hemagglutinin-esterase (65 kDa) that binds sialic acids at the surface of glycoproteins. The S glycoprotein determines the host tropism. There is indication that SARS-CoV-2 binds to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) expressed on pneumocytes [85,99]. Binding to ACE2 is expected to trigger conformational changes in the S glycoprotein allowing cleavage by the transmembrane protease TMPRSS2 of the S protein and the release of S fragments into the cellular supernatant that inhibit virus neutralisation by antibodies [100]. The virus is then transported into the cell through the early and late endosomes where the host protease cathepsin L further cleaves the S protein at low pH, leading to fusion of the viral envelope and phospholipidic membrane of the endosomes resulting in release of the viral genome into the cell cytoplasm. Replication then starts and the positive-strand viral genomic RNA is transcribed into a negative RNA strand that is used as a template for the synthesis of viral mRNA. Synthesis of the negative RNA strand peaks earlier and falls faster than synthesis of the positive strand. Infected cells contain between 10 and 100 times more positive strands than negative strands. The ribosome machinery of the infected cells is diverted in favour of the virus, which then synthesises its non-structural proteins (NSPs) that assemble into the replicase-transcriptase complex to favour viral subgenomic mRNA synthesis (see the review by Fehr and Perlman for details [101]). Following replication, the envelope proteins are translated and inserted into the endoplasmic reticulum and then move to the Golgi compartment. Viral genomic RNA is packaged into the nucleocapsid and then envelope proteins are incorporated during the budding step to form mature virions. The M protein, which localises to the trans-Golgi network, plays an essential role during viral assembly by interacting with the other proteins of the virus. Following assembly, the newly formed viral particles are transported to the cell surface in vesicles and are released by exocytosis. It is possible that chloroquine interferes with ACE2 receptor glycosylation, thus preventing SARS-CoV-2 binding to target cells. Chloroquine could also possibly limit the biosynthesis of sialic acids that may be required for cell surface binding of SARS-CoV-2. If binding of some viral particles is achieved, chloroquine may modulate the acidification of endosomes thereby inhibiting formation of the autophagosome. Through reduction of cellular mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase activation, chloroquine may also inhibit virus replication. Moreover, chloroquine could alter M protein maturation and interfere with virion assembly and budding. With respect to the effect of chloroquine on the immune system, see the elegant review by Savarino et al. [11]. ERGIC, ER-Golgi intermediate compartment.

Already in 2007, some of us emphasised in this journal the possibility of using chloroquine to fight orphan viral infections [10]. The worldwide ongoing trials, including those involving the care of patients in our institute [90], will verify whether the hopes raised by chloroquine in the treatment of COVID-19 can be confirmed.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None declared.

Acknowledgment

The figure was designed using the Servier Medical Art supply of images available under a Creative Commons CC BY 3.0 license.

Funding: This study was supported by IHU–Méditerranée Infection, University of Marseille and CNRS (Marseille, France). This work has benefited from French state support, managed by the Agence nationale de la recherche (ANR), including the ‘Programme d'investissement d'avenir’ under the reference Méditerranée Infection 10-1AHU-03.

Ethical approval: Not required.

References

E.A. WinzelerMalaria research in the post-genomic era

Nature, 455 (2008), pp. 751-756

CrossRefView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

A.R. Parhizgar, A. TahghighiIntroducing new antimalarial analogues of chloroquine and amodiaquine: a narrative review

Iran J Med Sci, 42 (2017), pp. 115-128

View Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

editor

L.J. Bruce-Chwatt (Ed.), Chemotherapy of malaria (2nd ed.), WHO, Geneva, Switzerland (1981)

WHO Monograph Series 27

N.J. White, S. Pukrittayakamee, T.T. Hien, M.A. Faiz, O.A. Mokuolu, A.M. DondorpMalaria

Lancet, 383 (2014), pp. 723-735, 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60024-0

ArticleDownload PDFView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

T.E. Wellems, C.V. PloweChloroquine-resistant malaria

J Infect Dis, 184 (2001), pp. 770-776

View Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

S.J. Lee, E. Silverman, J.M. BargmanThe role of antimalarial agents in the treatment of SLE and lupus nephritis

Nat Rev Nephrol, 7 (2011), pp. 718-729, 10.1038/nrneph.2011.150

CrossRefView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

D. Raoult, M. Drancourt, G. VestrisBactericidal effect of doxycycline associated with lysosomotropic agents on Coxiella burnetii in P388D1 cells

Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 34 (1990), pp. 1512-1514, 10.1128/aac.34.8.1512

CrossRefView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

D. Raoult, P. Houpikian, D.H. Tissot, J.M. Riss, J. Arditi-Djiane, P. BrouquiTreatment of Q fever endocarditis: comparison of 2 regimens containing doxycycline and ofloxacin or hydroxychloroquine

Arch Intern Med, 159 (1999), pp. 167-173, 10.1001/archinte.159.2.167

View Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

A. Boulos, J.M. Rolain, D. RaoultAntibiotic susceptibility of Tropheryma whipplei in MRC5 cells

Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 48 (2004), pp. 747-752

View Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

J.M. Rolain, P. Colson, D. RaoultRecycling of chloroquine and its hydroxyl analogue to face bacterial, fungal and viral infection in the 21st century

Int J Antimicrob Agents, 30 (2007), pp. 297-308

ArticleDownload PDFView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

A. Savarino, J.R. Boelaert, A. Cassone, G. Majori, R. CaudaEffects of chloroquine on viral infections: an old drug against today's diseases?

Lancet Infect Dis, 3 (2003), pp. 722-727

ArticleDownload PDFView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

J.R. Boelaert, J. Piette, K. SperberThe potential place of chloroquine in the treatment of HIV-1-infected patients

J Clin Virol, 20 (2001), pp. 137-140

ArticleDownload PDFView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

C. Huang, Y. Wang, X. Li, L. Ren, J. Zhao, Y. Hu, et al.Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan

China. Lancet, 395 (2020), pp. 497-506, 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5

ArticleDownload PDFView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

N. Zhu, D. Zhang, W. Wang, X. Li, B. Yang, J. Song, et al.A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019

N Engl J Med, 382 (2020), pp. 727-733

CrossRefView Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

P. Zhou, X.L. Yang, X.G. Wang, B. Hu, L. Zhang, W. Zhang, et al.Discovery of a novel coronavirus associated with the recent pneumonia outbreak in humans and its potential bat origin

bioRxiv (2020 Jan 23), 10.1101/2020.01.22.914952

H. Tsiang, F. SupertiAmmonium chloride and chloroquine inhibit rabies virus infection in neuroblastoma cells

Arch Virol, 81 (1984), pp. 377-382

View Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar